Some of you might be familiar with the concept that at the lowest level, all data in a computer is represented by 0s (zeros) and 1s (ones). This is quite spectacular to consider when you think about the many different formats computers can work with. For example, text, audio, and video. When you post a message on social media, or listen to a playlist on a digital music service, or watch a movie on a streaming service, all of that data is read by the computer as a sequence of 0s and 1s. But how does that work, exactly? How can something so simple power everything from tweets to streaming movies? I’d like to explore this with a rudimentary example. Yet to do that, I need to zoom out and talk a bit about…bits.

THE BASE-2/BINARY SYSTEM

The term “bit” is short for “binary digit.” This is the smallest unit in a base-2 numeral system. This is where those 0s and 1s come into play. Unlike the base-10 (decimal) system that most of us are familiar with, where 10 symbols (0 through 9) are used to represent the numbers, a base-2 or binary system only uses two symbols (0 and 1).

Here is a chart showing decimal numbers 1 through 32 with their binary equivalents:

+---------+--------+

| Decimal | Binary |

+---------+--------+

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 10 |

| 3 | 11 |

| 4 | 100 |

| 5 | 101 |

| 6 | 110 |

| 7 | 111 |

| 8 | 1000 |

| 9 | 1001 |

| 10 | 1010 |

| 11 | 1011 |

| 12 | 1100 |

| 13 | 1101 |

| 14 | 1110 |

| 15 | 1111 |

| 16 | 10000 |

| 17 | 10001 |

| 18 | 10010 |

| 19 | 10011 |

| 20 | 10100 |

| 21 | 10101 |

| 22 | 10110 |

| 23 | 10111 |

| 24 | 11000 |

| 25 | 11001 |

| 26 | 11010 |

| 27 | 11011 |

| 28 | 11100 |

| 29 | 11101 |

| 30 | 11110 |

| 31 | 11111 |

| 32 | 100000 |

+---------+--------+

If you look closely at the chart, you’ll see a pattern where the binary number gains a new digit at decimal values 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32. This happens because binary is positional, just like decimal. Except in decimal, every time you reach a power of ten (10, 100, 1000), you add a new digit. In binary, the rollover happens at powers of two, for example 10 (decimal 2), 100 (decimal 4), 1000 (decimal 8), and so on.

But don’t be fooled by the notation. Binary “10” is not decimal ten. It’s read as “one‑zero,” and its decimal equivalent is 2. Similarly, binary “1011” is not one‑thousand and eleven. It’s read as “one‑zero‑one‑one,” which equals decimal 11. It takes some getting used to if you haven’t encountered it before because we are so habituated to reading number notation according to the decimal system. Just remember, if you are reading binary, you read each bit as a one or zero.

A CONCEPTUAL BREAKTHROUGH

Before we go further, let’s pause to appreciate one of the great minds who made all of this possible, the “Father of Information Theory,” Claude Shannon.

Back in the 1930s and 40s, Shannon realized that the abstract rules of Boolean algebra (the math of true/false statements) could be directly applied to electrical circuits. In other words, he showed that switches flipping between “off” and “on” could represent logical operations. This insight was groundbreaking because it meant that binary wasn’t just a neat number system, but the perfect language for machines. Later, in his seminal 1948 paper A Mathematical Theory of Communication, Shannon laid the foundation for information theory, proving that all communication, whether text, sound, or video, could be measured, transmitted, and optimized using bits. Without Shannon, the bridge between theory and the digital world we live in today might never have been built.

THE PHYSICAL REALITY

At the physical level, computers use electrical signals to operate. These signals are measured as voltage levels. Digital circuits simplify them into just two ranges, low (0) and high (1). This binary mapping makes hardware reliable, because it’s far easier to distinguish between two clear states than it is to manage many possible voltage levels. What seems like a simple idea of representing information with 0s and 1s has a direct physical reality. Small fluctuations in voltage don’t matter, because as long as the signal is clearly “low” or “high,” the computer knows whether it’s dealing with a 0 or a 1. That’s why binary is such a natural fit. It maps perfectly onto the physical world of electricity not flowing (off) or flowing (on).

These voltage states directly control the hardware inside a computer. Transistors act as tiny switches that flip off or on depending on the voltage. When combined, they form logic gates, which use 0s and 1s to carry out Boolean operations like AND, OR, and NOT. By combining millions (or billions) of these gates, computers perform arithmetic, make decisions, and store information. From these simple building blocks, the vast complexity of modern computing emerges.

BITS IN ACTION

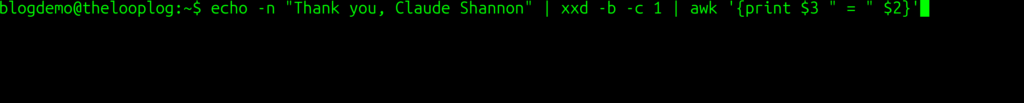

I want to demonstrate these principles using a simplified example that also allows me to play around in my Linux shell. Let’s take this idea of a bit representing an “off” or “on” signal, those zeros and ones of the binary system, and let’s limit our demonstration to text. I want to instruct my computer to reveal to me the binary that lies behind the characters I type. I can do this in Bash by running this command:

echo -n "Thank you, Claude Shannon" | xxd -b -c 1 | awk '{print $3 " = " $2}'

When I execute the command, this is what returns:

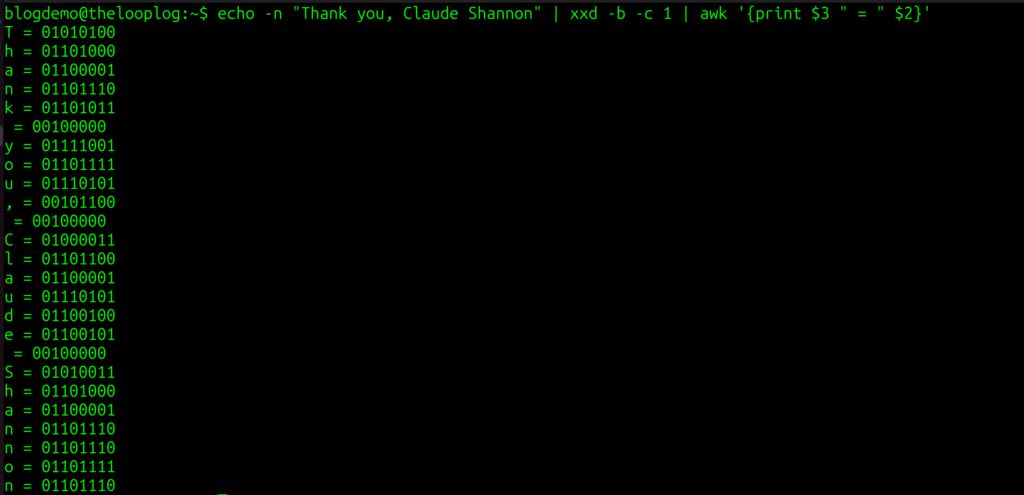

As you can see from the output of the command, every character within the double quotes is being displayed along with its corresponding binary number.

T = 01010100

h = 01101000

And so on.

Note that even the spaces and the comma have binary equivalents: 00100000 and 00101100 respectively. This is one way of making the abstract idea of bits concrete. Every letter, space, and symbol I type is stored and transmitted as a unique sequence of 0s and 1s.

Now let’s break down what this command is doing, and tie it back to the binary principles we’ve been exploring.

echo -n "Thank you, Claude Shannon"

echo prints text to the terminal.

The -n option prevents it from adding a newline at the end.

So this part simply outputs the string:

Thank you, Claude Shannon

#Pipe

|

The pipe takes the output of one command and sends it as input to the next.

Here, the text string is passed into xxd.

xxd -b -c 1

xxd is a tool that creates a hex or binary dump of data.-b tells it to show the output in binary instead of hexadecimal.-c 1 means “show one byte per line,” so each character is displayed with its binary representation.

Example output for the letter T:

0000000: 01010100 T

awk '{print $3 " = " $2}'

awk is a text‑processing tool.

In the xxd output, each line has multiple columns:$2 = the binary representation$3 = the character itself

The awk script rearranges them so you see:

T = 01010100

h = 01101000

...This command peels back the curtain. What looks like ordinary text is actually a series of binary codes with each letter, space, and comma mapped to a unique sequence of 0s and 1s. That’s the physical reality of bits in action.

THE SIMPLEST OF FOUNDATIONS

From Claude Shannon’s insight that Boolean logic could be wired into circuits, to the physical reality of voltage states flipping transistors off and on, to the binary codes behind every character you type, we’ve seen how the entire digital world rests on the simplest of foundations, 0s and 1s. What might look abstract on paper is, in fact, the most practical language ever devised for machines.

Binary’s elegance lies in its reliability and universality. Two clear states of low and high, off and on, false and true are enough to build logic gates, arithmetic, memory, and ultimately the vast complexity of modern computing. Whether you’re streaming a movie, posting on social media, or listening to music, it all reduces to sequences of bits flowing through circuits.

So the next time you tap a key or swipe a screen, remember that beneath the surface, your device is speaking the simplest language imaginable. And from that simplicity, the digital universe emerges.